Between Usual and Unusual: Regarding the Transition and Expression of Materiality In Material Painting

Author:Chen Yan Source:新美术,7th issue ,2016 Release time:2022-11-15ABSTRACT: This essay uses the artworks of Gunther Uecker and Josepha Gasch-Muche to discuss a media concept that stands between the two extremes of “media transparency” and “media is art” as well as the consequential experiences with its influences. The article further explores the possible relationship between art media and the nature of art.

Keywords: painting with Comprehensive materials, media materiality, transition and expression

The connection between artwork and its media is of great significance in the philosophy of art. Judgements on such relationship is the prerequisite of art interpretation and art appreciation; artistic creation would further more require the mastery of it, under which exist two extreme points of view [1]. One extreme is “media transparency”, where well-trained artists uses paint to depict anything they want; the audience look through the paint, ignoring it, to fully focus on the object of depiction and perceive the imagery. When the image of perception conforms to the motif, illusion is created. This illusion conflicts with the detection of media, under which condition the illusion would be obliterated; therefore, the media shall be invisible. Another extremity of the spectrum is, represented by Jackson Pollock’s drip technique, that paint shall not be subordinated to and serve the artistic theme nor should it be hidden, insisting that “painting is paint” and materials should unify with the theme. Painting is no longer an imitation or representation, but the spontaneous expression of paint itself.

Historical backgrounds and cultural perception are the presupposition, vitality and lifecycle of theories. Due to their universal recognition, the artistic influences and historical missions of the two theories — “media transparency” and “media is art”— will be omitted. This article intends to concentrate on the artistic exploration in between the two opinions.

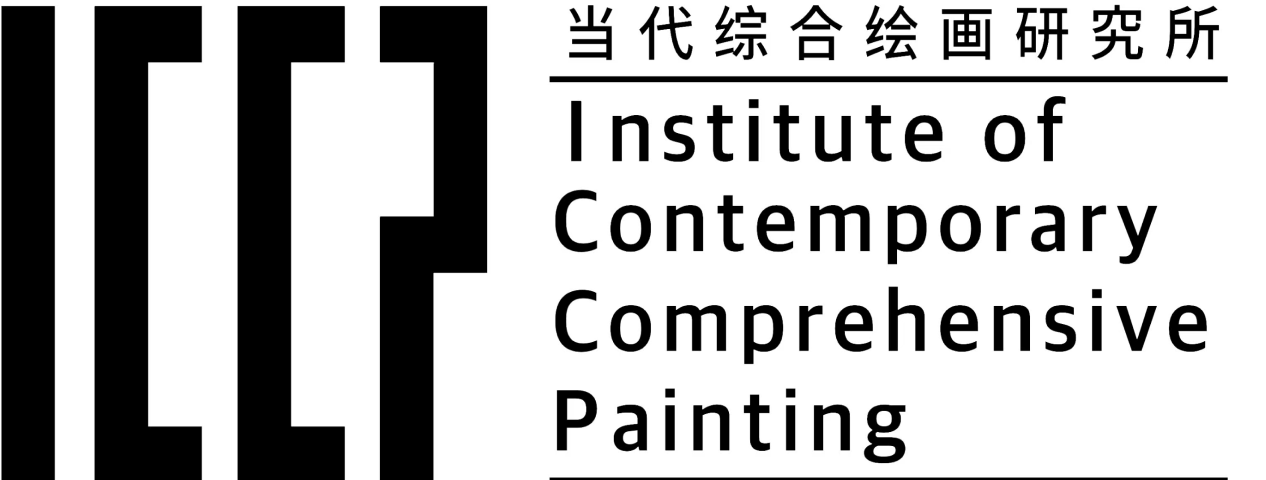

The first to introduce is German artist Gunther Uecker and his works with nails. The array of nails on wood planks and canvases created with a two-dimensional inclination, reminiscent of tapestry, profoundly impressing the audience. A cold, sharp and mundane object familiar to all, nail is often used to bound multiple objects together; it could also be used to invade and hurt others, as in the well-known crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Therefore, nail is assigned a threatening cultural moral. Using methods of repetition and construction, Uecker dispelled nail’s functional stereotype and the menacing psychological suggestion. In a trance, one could feel that the clusters of nails become soft and subtle embodiment such as waterdrops, fog, seeds and fluff. Such presentation has successfully achieved the alternation of objects’ characteristic and directional meaning, from individual level measure to collective level.

Illust.1

1964 . White Field.Gunther Uecker . Tate

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/uecker-white-field-t00684#0

Illust. 2

Günther Uecker, New York Dancer I, 1965.

Nails, cloth, and metal with electric motor, 200 x 30 x 30 cm.

Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. © Günther Uecker. Photo: Bruno Bani, Milan

https://www.guggenheim.org/audio/track/gunther-uecker-new-york-dancer-i-1965

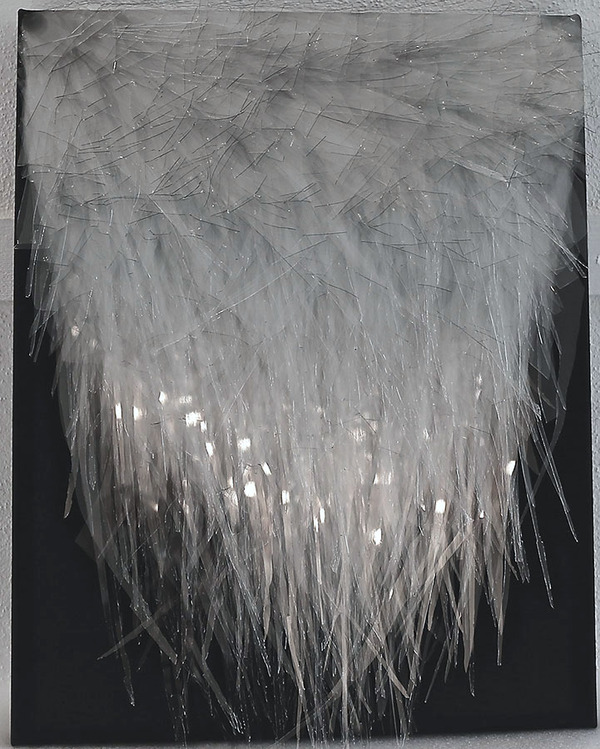

German artist Josepha Gasch-Muche, who uses thin glass shards to compose, is another representative [2]. Large amount of glass flakes, shiny or matt, transparent or dyed, were glued together staggered and in geometrically to appear in overall shapes of squares, triangles, circles or even cubes and pyramids. Her expression of using inconsistent, multi-directional broken glasses to model ideal geometry overall-presentation fits Benoit B. Mendelbrot’s naturalism[3]: One would always, no matter how magnified, observe irregularity in topographies of mountains and coastlines. Through the multiple and amplified reflection, refraction and diffraction of glasses, Gasch-Muche’s artistic structure displays a kaleidoscope of shifting lights as well as strong impact on audience’s psychology — that the boundary between the regular and the irregular, the certain and the random, the still and the moving — can be so blurred. Thus, the advanced, platonic “notions” — analysis, recognition and understanding — are shaken by the tremendous uncertainty and complexity; another perceptual experience regarding light and dark, cold and warm as well as light and heavy, occurs spontaneously. An emotional and speculative viewer might be brought into a philosophical and ethical questioning: Is the black and white in the art a metaphor for those that are contradictory-like the alternation of day and night, the Daoism contrast of existence and nihility, a moral battling of the good and the evil? Or, on another sense, the reflection of our impermanent life — the highs and the lows, failures and successes, pains and dreams?

Illust. 3

02/06/09, 2010; 40 x 40 x 40 centimeters; glass, graphite, wood.Josepha Gasch-Muche

https://contempglass.org/artists/entry/josepha-gasch-muche

Illust. 4

05/11/14, 2014; 60 x 50 x 10 centimeters; glass on canvas.Josepha Gasch-Muche

https://contempglass.org/artists/entry/josepha-gasch-muche

Rather than telling us what has been already known, in Hamlet’s style, Uecker’s nail and Gasch-Muche’s glass shards could be seen as the tools or media that helped our self-perception. Propositions in styles Propositions made in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus style only allow us to talk about the world, but give no permission for us to speak as the world[4]. Uecker and Gasch-Muche’s artistic practice can be seen as the artistic response to Wittgenstein’s philosophy of logic. Gasch-Muche, on one hand, broke the dull, decorative routine of utilizing the optical properties of glass. By complicating the mediatic structure of glass, its transmission characteristics have been complicated likewise. Consequently, artists construct and deconstruct to create optical illusions, forcing the audience to redefine and reflect on concepts such as reality, appearance and illusion. Uecker’s works, on the other hand, consist of sharp nails that could have been seen as the symbol of aggressive males; however, they are grouped and fixated on surfaces, passing its life in obscurity. Such contrast of form and symbolization puts ordinary media into strong conceptions, deconstructing the masculine, hegemonic gender and social symbols with the magnified of collectivism.

Artists transformed the natural property of artworks’ media from familiar to unfamiliar, merging organically into the works’ intentions, generating a new possibility or even a new profound experience. While one could say that Cézanne’s works represents generative construction of visual activity, where color-conditioning presents the production of each colorful façade and its relevancy to the surroundings so much as the consequential, connective affiliation, Uecker and Gasch-Muche’s practices brings another generative, profound experience with their process of media. In Uecker’s arts, every nail cluster and its surrounding ones are parts of a continuum, with the said relationship maintained on nonplanar “bases” like tables and chairs. Such style even attracted cross-disciplinary attention; Philip Gaskell from the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge University mentioned the characteristics of Uecker’s nail matrixes, that every nail is seemingly randomized microcosmically but ordered at a medium-scale level, changing ever so slightly in angle accordingly[5]. Gasch-Muche’s methods possess similar partial and holistic harmony; different in shapes, the glass shards form a complicated optical labyrinth system, filled with the paradoxical tension of recognizable outline and anisotropic structure.

In our experience, if one use gaze to surround and sink into objects, it is possible to pull over all sides of a three-dimensional object, cancelling its depth; one can also shift the gaze sterically without changing the object, only to separate it from the restriction of perspective so that the details could be more concealed or revealed. This method can possibly give particularity to depth to differentiate from other dimensionalities. At this moment, depth is “the dimension in which the components of objects can coexist in mutual-tolerance, with height and depth being the dimension of juxtaposition”[6]. Depth represents the inseparable relationship between the object and the fact that I am able to stand in front of it. To artists, such relationship is seen in between “oneself” and the observation of objects, which can be visualized by the adeptness of sketching and coloring; one can also increase the dimension of expression by emphasizing mediatic materials (Uecker’s nails and Gasch-Muche’s glass shards), exploring the possibility of picturizing the abovementioned relationship. In this case, depth does not belong to objects but to visual aspect; only a world which solely comprised of vision could such phenomenon exist. Therefore, depth, more than any other dimensions, requires us to discard all prejudices against the object in front of us in order to rediscover the initial experience of the world manifesting itself. Depth is, fundamentally speaking, the distance between the object and “myself”. Just as Maurice Merleau-Ponty pointed out in Phenomenology of Perception: “Among all dimensions, depth possesses the most traits of ‘existence’.”

Arthur Danto claimed that besides all standard aesthetical predicates exists a whole system of predicates, whom are only applicable to artworks but not to commonplace. In this sense, these predicates are neither suitable for the material counterpart of art, aka media. When media become a necessity of art and even to the extent that the interpretation of art become inseparable from the analysis of its mediatic properties, questions shall be raised: how applicable is the predicate system to artworks but not to media? Where should the boundary be? When comprehensive painting attempts to utilize media in the fashion of mediatic transformation rather than simply piling up substances, will it connect with the said predicate system and in what way? How would such new transformation and expression reform the system?

We might use a subtitle from Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time as the answer to the possible solution to the question of media — Art relationship: the existential analytic and the interpretation of primitive Dasein: the difficulties in securing a “natural concept of world”.

References:

1. [美]阿瑟·丹托著,陈岸英译,《寻常物的嬗变—一种关于艺术的哲学》,江苏人民出 版社,2012 年.

2. Josepha Gasch-Muche, Josepha Gasch-Muche, Distanz Verlag, Germany, 2014.

3. Benoit B. Mandelbrot, The Fractal Geometry of Nature, W.H.Freeman and Co. Press,1982.

4. [英]路德维希·维特根斯坦著,张申府译、陈启伟校,《逻辑哲学论》,北京大学出版 社,1988 年。

5. Philip H. Gaskell, “Medium-range order and random networks”, in Journal of Non- Crystalline Solids, 2001, pp. 146-152.

6. [法]梅洛-庞蒂著,姜志辉译,《知觉现象学》,商务出版社,2012 年.

This article was first published on the CAA academic journal New Arts, 2016, Issue 7th, page 91-93